Dear E.T.,

I hope there is going to be a E.T., 2. I loved the movie E.T., it was exciting. I liked when you were riding on the bike, and thanks for not dying.

Your friend,

Jonah

P.S. Next time your in the neiborhood, E.T., phone me.

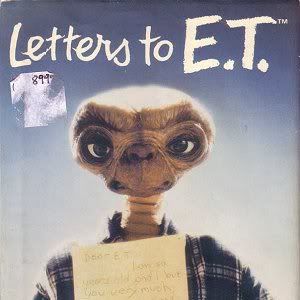

That awkwardly written yet undoubtedly sincere missive comes from a book called Letters to E.T. (Putnam, 1983), a slim volume which I was fortunate enough to locate in a dusty, cluttered second-hand bookshop in Chicago last May. The book, a somewhat hastily assembled collection of fan mail and fan art, is a quaint souvenir of the E.T.-mania of 1982 and 1983. I remember that mania well, as I was swept up in it like most kids my age at the time. You can bet that there were some E.T. toys under the Christmas tree in the Blevins household back in December '82. I had the leather-skinned E.T. doll (now an eBay item) and a little plastic replica of the film's young hero, Elliott, riding on a bicycle with his alien friend, E.T., wrapped up in a blanket in the bike basket.

It's hard to say what place E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial holds in pop culture today. The film currently rates a 7.9 at the Internet Movie Database and does not appear on that site's Top 250 list, though it does occasionally merit dutiful inclusion on those meaningless G.O.A.T. (greatest of all time) lists released by Entertainment Weekly or the American Film Institute. It did reign for several years as the all-time box office champion, but such records do not and cannot last. (And then there are always those people who want to bring up inflation and rising ticket costs.) Perhaps because it was not the beginning of a multi-film/multi-media franchise and does not afford nostalgic adults the opportunity for elaborate dress-up games (as does Star Wars), E.T. now occupies an ever-shrinking space in the public's imagination. If anything, the movie might seem to be just another corny relic of the fad-happy 1980s, the cinematic equivalent of moonwalking or the Rubik's Cube -- fun at the time but something we've outgrown as a society.

My first intention, in fact, when I found Letters to E.T. was to use the book as the basis for a satirical piece for Unloosen. I was going to take on the role of an embittered, washed-up E.T. and finally answer those quarter-century-old fan letters in the most depressing, cynical, and alcohol-fueled way possible. Essentially, I was going to write E.T. as if he were William Holden. That idea struck me as funny, but the article never got written. As Craig will attest, I work very slowly and procrastinate whenever possible if there is no self-or-otherwise-imposed deadline weighing on me. The book stayed on the desk next to my bed for months, and during that time I must've spent several accumulated hours poring over its pages as I drowsed off. Not that the letters were particularly eloquent or moving, mind you -- that one above from Jonah is one of the stronger examples -- but the book held some intangible fascination for me nevertheless. Maybe it was because the letters were addressed directly to the film's title character, which seemed to suggest that the film held some kind of special power over its young viewers. Intrigued by the book, I decided to return to the movie itself and was quite surprised at what I found. Once I had revisited E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, I no longer wanted to write the satire but I did want to write about the film in some way. This project seemed as good an excuse as any.

(Please note that my comments from here on refer to the original 1982 version of the film and not the tampered-with 2002 reissue.)

E.T. caught me off guard from its opening seconds. The main title sequence is exceedingly stark: just unadorned text against a plain backdrop, practically as sober as an Ingmar Bergman film. (Side note: Notice how Bergman, by keeping his opening credits ultra-plain, inadvertently created some of the most stylish title sequences of all time, memorable enough to have been copied by Woody Allen and parodied by Monty Python.) Although E.T. is remembered for its cuteness and sentimentality, John Williams' title music -- part of a score which does not get enough credit for its variety -- is not cute or sentimental at all. In fact, it's decidedly eerie and a little foreboding. An audience seeing this film for the first time and having no advance knowledge of its plot might reasonably think they were about to see something scary, perhaps a sci-fi horror tale.

From its very first scene, E.T. skillfully demonstrates how to tell a story through moving pictures, and I think the film would be comprehensible even if viewed with the sound off. The film proper begins with a dialogue-free sequence that serves as a master class in visual storytelling. I have to congratulate director Steven Spielberg, his cinematographer Allen Daviau, and perhaps most of all his editor Carol Littleton, for the job they have done here. There's a quietly brilliant series of shots that completely drew me into the film's world and its storyline. First, we see the night sky. Then a stand of trees. And then, suddenly, we cut to a spaceship, a huge glowing orb parked serenely in the forest like it's supposed to be there. The nonchalant, matter-of-fact introduction of that spaceship is an early indication that E.T. will deviate from the standard mold of sci-fi fantasy films. I was taken aback by the film's low-key intimacy. "Low-key" and "intimate" are not adjectives normally applied to films on the "all-time blockbusters" list, especially PG-rated sci-fi fantasies aimed at the widest-possible audience. In contrast, think of Star Wars, the movie that E.T. temporarily displaced as the #1 moneymaker in history. (The Star Wars franchise is affectionately referenced throughout E.T.. I particularly enjoyed the very true-to-life detail of how the young hero's Star Wars action figure collection seemed to mostly contain the obscure Lucas characters -- Greedo, Hammerhead, Walrus-Man -- which for some reason were much more plentiful in toy stores than the main characters.)

As the story unfolded from there, I was reacquainted with the fact that E.T. is a surprisingly complex film that adroitly captures many moods. By turns, the film can be funny, playful, awe-inspiring, heroic, and deeply sad. To illustrate how well the film does all this, I will discuss the film's "Halloween night" sequence in some detail. To recap the plot to this point: a race of peaceful aliens have visited the planet Earth (specifically the Los Angeles of 1982) in order to study our plant life. But as they're collecting samples of the local flora, some government scientists (led by Peter Coyote) show up and scare them away. One alien, who will later be dubbed E.T., is left behind -- stranded on our planet with no home and no one of his own kind nearby. Cautiously venturing into the suburbs, the alien soon befriends a small boy, Elliott (Henry Thomas), with whom he quickly establishes a powerful psychic bond. Elliott allows the alien to live in his room and only divulges the alien's existence to his older brother, Mike (Robert MacNaughton), and his younger sister, Gertie (Drew Barrymore). The three children manage to keep the alien a secret from their overtaxed mother, Mary (Dee Wallace), who is currently undergoing a painful separation from her husband, the children's father. The children teach the alien the rudiments of English, and Elliott figures out that E.T. wants to build a "phone" with which he can call his home planet. Eventually, rummaging through their own toys and whatever they find in the garage, the kids cobble together enough equipment to assemble the phone. E.T. now needs to travel back to the woods where he originally landed in order to set up the equipment. Elliott must accompany him, and the kids decide to use Halloween night as their opportunity. They will sneak E.T. out of the house by dressing him as a ghost and passing him off as Gertie. (The real Gertie will be waiting for them at an agreed-upon lookout spot.) Once safely away from the neighborhood, E.T. and Elliott will travel by bike to the woods to set up the phone.

Got all that?

The "Halloween" portion of the movie starts out as a natural and observational look at American family life. While carefully applying his costume's face paint, Elliott squabbles with Gertie over the specifics of their plan. Gertie, eager to be taken seriously, tells Elliott she's "not stupid" as children have been insisting to their siblings for generations now. In the background, Mary and Mike can be heard arguing about Mike's plan to trick-or-treat dressed as a terrorist. Once everyone is in costume and the plan is underway, the film turns lightly comic. The costumed E.T. -- a natural for physical comedy with his rotund physique and waddling walk -- has trouble staying upright when Mary takes a Polaroid picture of her "three" children. There is some suspense, too, as E.T. threatens to blow their cover by trying to magically "heal" Mike's fake knife wound. The humor continues as Mike and Elliott accompany E.T. through the local streets which are densely occupied by costumed trick-or-treaters (E.T. misidentifies a "Yoda" as a possible alien compatriot), but there is a touch of surrealism here, too. Allen Daviau takes full advantage of the uncanny orange dusk light of the hour, and that, combined with the device of showing the events from E.T.'s perspective (low to the ground and seen through the holes in his bed sheet), gives the trick-or-treat sequence an otherworldly, disorienting oddness heightened by John Williams' wry score. Halloween is such a normal American ritual that we may forget how elaborately odd it all is. Spielberg reminds us with this scene. Eventually, the kids do get to the meet-up spot, and Elliott puts E.T. in his bike basket and takes off through the woods. Here, the film turns into a more-serious adventure yarn: the quest or hero's journey. After a while, Elliott can go no further on his bike and insists that they must continue on foot. E.T. has other ideas and miraculously levitates the bike so that he and Elliott can fly through the sky. Of course, the image of Elliott and E.T. silhouetted against the moon is not only the emblem of this film but also of Spielberg's Amblin production company. It's a monumental moment in pop culture history. The alien had levitated objects previously in the film but nothing of this magnitude. Fittingly this is the first time we get to hear John Williams' famous E.T. theme in full. Up to this point, Williams had been doing a marvelously clever job of parceling that theme out a little at a time, so it's especially powerful when we finally hear the full-blown version.

But Spielberg contrasts this moment of triumph with glimpses of anguish, anxiety, and paranoia. While E.T. and Elliott are out in the woods, Elliott's mother Mary is home, worried sick about her missing child. Spielberg takes a moment here to watch Mary and she sadly extinguishes some Halloween candles and stares worriedly at the clock. Once she leaves the house to look for Elliott, the film takes another turn. The faceless, possibly threatening government agents turn up at the family's house and begin searching through it. Here, the film takes on the feel of a horror/suspense thriller, as the agents are seen only in menacing outlines. Meanwhile, their flashlights cast dreadful-looking shadows on the walls and give even Gertie's toys a menacing look. When the film rejoins Elliott and E.T out in the woods, the mood is briefly hopeful -- the homemade "phone" seems to be working -- before giving way to disappointment as there is no immediate response to the signal. The intense and moody Elliott is at his saddest and most vulnerable here, as he pleads with E.T. to remain on Earth. "We could grow up together!" Elliott desperately suggests. Henry Thomas' performance as Elliott is admirably nuanced, and Spielberg coaxes some shockingly honest and painful moments from him. And keep in mind, all of what I've described in this Halloween sequence occurs in a relatively short amount of screen time. The next part of the film deals with the decidedly gloomy aftermath of that night, as a bedraggled Elliott finally returns home while E.T. lies near death in the woods.

What struck me time and again about E.T. is, in contrast to most mega-blockbusters, how private and personal it all felt. And quiet, too. This is a remarkably quiet movie, mostly by necessity of the plot. This is a film that takes place largely within the secret, insular world of children, and much of the dialogue is spoken in hushed, muted tones. As I get older, quietness is one of the qualities I admire most in films, and it's especially wonderful when an audience allows a film to be quiet. I wanted to include E.T. in our "Family Films Month" partly to show that all-ages films do not necessarily have to be raucous and relentlessly zany for their entire running times. We seem to have forgotten that. Credit for the film's tone must largely go to its creator. Steven Spielberg has said that E.T. was his most personal film, the one closest to his heart, and revealed that the plot was inspired by his own parents' divorce. The film's fine, sensitively written screenplay is credited to Harrison Ford's then-wife Melissa Mathison. Spielberg dictated the plot to her while they were on location for Raiders of the Lost Ark. Another big factor contributing to the film's tone is the unique look achieved through lighting and cinematography. Just as I was surprised by how quiet the film often was, I was pleasantly surprised at how dark -- literally dark -- it is allowed to be. The movie mostly takes place within a suburban home, and it is a moody, shadowy, decidedly non-sitcom-y environment with almost noir-ish light coming through venetian blinds. Again, these days, a film aimed at kids would be almost blindingly bright and cheerful-looking.

The term "non-sitcom-y" could apply to the entire movie. The dialogue sounds off-the-cuff and authentic -- the kind of stuff that kids would really say and not the kind of contrived schtick a Hollywood screenwriter would normally write for them, packed with well-timed zingers and snarky pop culture references. (For a handy tutorial in how little kids talk in movies these days, watch Sandra Bullock's youngest son in The Blind Side.) E.T. is a very observational film with an almost documentary-like feel at times. Sometimes, it feels like we're spying on the characters or that we're being allowed to look in on something secretive and hidden. I appreciated how the movie took its time to establish the characters and let the plot build and progress naturally. It does not feel like the movie is going out of its way to "wow" us with something spectacular every 5 to 10 seconds. The characters are just allowed to be themselves, and the movie lets us observe them at moments which do not necessarily advance the plot. Among many examples (such as the aforementioned scene with Mary and the candles), I will cite a brief scene in which Elliott's older brother, Mike, retreats to an upstairs closet full of toys, curls up in the fetal position, and falls asleep. He does all this while his brother and E.T. are both being observed by a team of doctors and scientists downstairs, and I think it's his way of coping with the stress and insanity of the situation by retreating to the safety and security of early childhood.

Returning to E.T. in 2010 was eye-opening. The film is not campy or kitschy and does not feel dated. Within the framework of a familiar fish-out-of-water story, Spielberg manages to give us a portrait of a sad, intense kid -- who seems to have no other friends besides his own siblings -- struggling with the dissolution of his parents' marriage. I think the one thing that made me want to write about the film for this project is the film's final shot. Spielberg shot the film largely in order so that the young actors' reactions would be genuine during E.T.'s departure. The proof that his plan worked is right there on screen. The next time you happen to watch this movie, check out the expression on Henry Thomas' face in that very last shot. You can't make this stuff up.

If there's one thing that Hollywood has proven time and time again, it is that there is no film so perfect that it can't be improved upon at a later date when special effects technology has caught up with what its filmmakers originally intended. And if there's one thing that critics and audiences have proven, it is that they will unquestioningly lap up anything that puts a new spin on a beloved classic. This is why Lucasfilm's enhanced version of the original Star Wars trilogy was universally acclaimed when it was released in theaters and came to DVD, effectively supplanting the older editions, and Ted Turner was hailed as a visionary genius when he announced that he would be colorizing all of the black and white films in his vast movie library. After all, what good is a masterpiece if nobody wants to watch it because the effects are kinda hokey or it was shot before color film was the standard? (Never mind that many early silents were actually tinted. In fact, never mind silents, period. Who wants to watch a movie starring a bunch of mutes anyway?)

This brings us to Steven Spielberg's classic family film E.T. The Extra Terrestrial, the blockbuster that won the hearts of millions in 1982 and which Spielberg decided needed a digital overhaul for its 20th anniversary re-release. (Of course, this was not the first time Spielberg had tinkered with one of his creations after the fact. 1977's Close Encounters of the Third Kind begat 1980's Special Edition and a 1998 Director's Cut that split the difference between the two.) Unlike Joe, however, I have no choice but to comment on the 2002 reissue of E.T. since that was only version that was readily available to me. While my local library has nine copies of the film in its collection, every single one of them is the one-disc version with the distracting digital effects and an E.T. that is far more mobile and expressive than he was when he first lumbered across movie screens in 1982. Not to put too fine a point on it, but this is quite literally not the film I saw when I was eight, going on nine.

Before the opening credits started, I noted that the film was rated PG "for language and mild thematic elements." As far as the language is concerned, there's one "douche bag" early on, someone gets called "penis-breath" and there's even one "shit" that managed to slip through the net. (Why Spielberg would digitally remove all the guns from the film but leave the profanity intact is puzzling to me.) On the "mild thematic elements" front, I imagine that refers to the scene where E.T., left to his own devices, gets drunk on beer and Elliott, who is at school at the time, feels the effects because of the psychic bond they share. That's the first time the connection between them is made explicit in the film and Elliott's acceptance of their Corsican Brothers-like predicament comes to a head later on when E.T. is ailing and he says, "We're sick. I think we're dying." I don't care what age you are when you see this film; like the divorce trauma percolating under the surface of the story, that's a pretty heavy thing to lay on an audience expecting a lighthearted fantasy.

Then again, as Joe says, the film's opening is rather on the ominous side, especially when it comes to its treatment of the faceless government agents that are on E.T.'s trail once its ship has to take off without it. Of the dozen or so men in pursuit of their alien quarry, only one is given a calling card -- a jangling set of keys -- so we can identify him later on when he is revealed to be second-billed Peter Coyote, who plays E.T.'s equivalent of the Dick Miller role in Joe Dante's Explorers. In fact, in many ways E.T. is like the inverse of Explorers since it concerns itself with an alien stranded on Earth sending a message out into space so it can get picked up by its own people, as opposed to an alien broadcasting a message from space to get some Earthlings to come to it. (Curiously enough, both films feature scenes from This Island Earth that are shown on TV. I guess that must have been a seminal film for both Spielberg and Dante.)

The pop-culture cross-pollination doesn't stop there, either. For example, the scene where E.T. hides from Elliott's mother amongst a horde of stuffed animals is echoed in Gremlins in the scene where Stripe hides from Billy in the toy aisle of the department store -- and behind an E.T. doll. Then there are the Star Wars action figures and costumes that Joe mentioned, but I was more impressed by the Space Invaders T-shirt older brother Mike wears and the way he sings Elvis Costello's "Accidents Will Happen" when he arrives home from football practice. (There's even an Elvis Costello poster on the wall in the room he shares with his younger brother. Note the bunk beds in the scene where Elliott first shows E.T. to his siblings.) And it's impossible to ignore the parallels to Peter Pan (which Spielberg also explicitly invoked in A.I.) since their mother Mary (whose name could even be a Biblical reference -- is Elliott's absent father named Joseph?) is heard reading it aloud to Gertie. This sets up the beat right after E.T. dies when Gertie asks, "Can we wish for him to come back?" I'm sure most people in the audience are thinking the same exact thing at that exact moment.

I'm afraid I don't have as much to say about this film as Joe does. Maybe it's because I kept getting wrenched out of the story every time one of Spielberg's much-ballyhooed digital "improvements" showed up on screen, but it just didn't resonate with me the same way it did when I was a kid. At some point I'd like to get my hands on the two-disc edition that was released in 2002 (and which included the original vision of the film -- unlike George Lucas, Spielberg wasn't as intent on denying people the option if they wanted it) to see if it works any better for me. Then again, whenever I see a full moon nowadays, my thoughts turn to howling beasts in the forests, not benevolent aliens from the skies. Not sure what that says about me, but at least I haven't abandoned the realm of fantasy entirely. That's one way E.T.'s legacy endures.

Next up: Family Films Month continues with a movie featuring a bunch of Muppets, and I don't mean Return of the Jedi.

I revisited Return of the Jedi somewhat recently, and I found it to be the Star Wars equivalent of Superman III -- which is actually more a compliment than an insult. They're both crazily overstuffed movies with lots of randomness going on. They're certainly not as serious and tidy as hardcore fans might want them to be, but they're also quite a bit of fun. The plots even have some parallels. In both movies, the hero (Luke Skywalker/Superman) is going through a big emotional identity crisis leading to a climactic showdown (with Darth Vader/Evil Superman), and meanwhile there's lots of comedic shenanigans going on in other parts of the movie (Ewoks/Richard Pryor). I enjoyed both of them, to be quite honest.

Looking back over our comments, I'm amazed that neither of us thought to mention the huge boost in popularity Reese's Pieces had as a result of their association with this film. (Checking my notes, I do see "Reese's Pieces product placement" scribbled right above "penis-breath" -- not that I think eating Reese's Pieces makes your breath smell like penis, mind.) I realize this wasn't the first instance of product placement in a motion picture, but it did set the standard for what was possible when it was done right. Three years later I recall dutifully consuming a goodly number of Baby Ruths (despite the fact that I much preferred Whatchamacallits) just so our family could get enough proofs of purchase to send away for a poster of Chunk and Sloth sharing the candy bar in The Goonies (which, now that I come to think about it, was also produced by Spielberg). I don't think I've eaten once since.

Weirdly enough, Reese's Pieces didn't make much of an impression on me this time around. If I thought of them at all during the movie, it was because of their repeated use on Family Guy as bait to lure James Woods into a trap. ("Ooh! Piece-a-candy!")

The little pop cultural things that jumped out at me this time were the Sesame Street cartoon with Casey Kasem's voice and the use of the song "Papa Oo Mow Mow." The "Papa Oo Mow Mow" thing is really a neat touch because, to me, it's an example of how the movie is just content to be observational. When Mike and his friends are sitting around the table playing a game, everybody's talking over everybody -- the way real kids do -- and if you're listening, you can hear one of the kids call into a radio station and request "Papa Oo Mow Mow" for Mike's mom. And then, a few minutes later you can hear that song playing very faintly in the background. They don't turn up the volume and have the kids sing along or anything, like they're trying to sell you an oldies-laden soundtrack LP. It's just part of the hustle and bustle of the day. What struck me about the song itself is that the radio station opts for the Persuasions' excellent and somewhat obscure acapella version and not the more-familiar Rivingtons original, to say nothing of the Trashmen's megahit reimagining of the song as part of "Surfin' Bird." (For those who don't know, the Trashmen combined two Rivingtons songs, "Bird is the Word" and "Papa Oo Mow Mow," to make "Surfin' Bird." In retrospect, it was one of pop music's very first mashups.)

Richard Pryor would never have gotten the deflector shield lowered in time, and Wicket would surely not have thought to put "tar" in Kryptonite.

Also, wasn't "Penis Breath" the original working title for "Pretty Woman" ?

I don't know about that, but I'm pretty sure the original slogan for Snickers candy bars was "Packed with penis, Snickers really satisfies."

I'm glad Speilberg didn't remove the "penis breath" line from the movie because it helps to reveal character -- both of Elliott and his mom, Mary. Elliott clearly doesn't know what he's saying. Kids are obsessed with profanity and sexual terminology even if they don't totally get what it means. For instance, there's a later scene at a bus stop where some of the older kids taunt Elliott with jokes about his supposed "alien" being from "Uranus." One kid repeats that joke over and over -- "Get it? YOUR Anus?" -- until his friend tells him that Elliott doesn't get it and they move on. But Elliott knows enough to know that, whatever "penis breath" means, it's a very strong and offensive term. It's a measure of how messed-up Elliott is at this point -- reeling from the loss of his father and out of step with other kids his age -- that, out of frustration, he yells it to Mike not only IN FRONT OF HIS MOTHER but also AT THE DINNER TABLE, which to me makes it like the kid equivalent of dropping a nuclear bomb. His mom, Mary, is so taken aback by Elliott's shocking breach of protocol that all she can do is laugh, which actually helps to defuse the situation.

Another good, true moment in the movie.