"Oh, my gosh. Does that suck?" - FRANK XAVIER CROSS, a man who knows how to inspire confidence in his underlings

If there is a holiday story that has been brought to the screen (both big and small) more often than Charles Dickens's A Christmas Carol (either in its original form or one that has been modernized, reimagined or otherwise parodied), I don't know what it is. The '80s alone brought us Mickey's Christmas Carol (with Uncle Scrooge in the role he was born to play), a well-regarded made-for-TV version starring George C. Scott (one of several made that decade, in fact), and Blackadder's Christmas Carol, not to mention various television shows and specials. I fondly recall an episode of George Burns Comedy Week from 1985 entitled "Christmas Carol II: The Sequel" in which we find out that Bob Cratchit (Roddy McDowall), Mrs. Cratchit (Samantha Eggar), a very grown-up Tiny Timothy (Ed Begley Jr.) and others have been taking awful advantage of Ebenezer Scrooge (James Whitmore) since his change of heart, prompting the three ghosts to pay him a return visit and show him how to find the middle ground between being a heartless miser and letting everyone walk all over him. In fact, A Christmas Carol parodies are so ingrained in the culture at this point that they don't even need to be tied specifically to the holidays, as seen in last year's Ghosts of Girlfriends Past and 2008's liberal-bashing An American Carol. And this doesn't even take into account all of the stage and radio productions, some of which have taken their own liberties with the story, so finding a new slant on it can be a pretty tall order. (Has somebody done a version that takes place in space yet? If not, they probably will now.)

Which brings us to the final entry in our year-long series, which appropriately enough is centered around Scrooged, the 1988 fantasy-comedy that somehow got sidetracked on its way to becoming a perennial holiday classic. Oh sure, it still shows up on television year in and year out (most Christmas movies do, regardless of their age or quality), but you won't find any channel airing it for 24 hours straight the way TBS does with A Christmas Story (a tradition going back 14 straight years), and it certainly isn't accorded the respect that It's a Wonderful Life's twice-yearly airings earn it (a far cry from its near-ubiquity back in the '80s before its copyright was reasserted). Regardless, it's about the only Christmas film that gets to me on a gut level in spite of the cloying sentimentality that periodically threatens to overwhelm the whole enterprise. Not that I want to be a total Scrooge about it, but this is one film that works a whole lot better when it isn't forcibly ramming holiday cheer down people's throats. And it could use a little less slapstick. Check, make that a lot less slapstick.

My first clue that the version of Scrooged that made it into the multiplexes wasn't all it could have been was found in the liner notes of Danny Elfman's Music for a Darkened Theater: Film and Television Music Volume One, which was released in 1990. The compilation is made up of short suites (sometimes comprising only the title music) from his first dozen or so film scores (along with the theme songs for The Simpsons and Tales from the Crypt), but Elfman reserves the longest section (close to nine minutes) for Scrooged, which to my knowledge has never been released in any other form. Some of Elfman's notes are short and to the point (on Back to School's cheerful "Study Montage": "Silly piece of music but I'm still fond of it.") while others are short and diplomatic (regarding the little-loved Bobcat Goldthwait talking-horse comedy Hot to Trot: "I never pass up the opportunity to write for accordions."), but there's only one case where he really sounds regretful. Here's what he had to say about working on Scrooged:

"The original tone of this film, as you can hear in the music, was much darker than what ended up on screen. Although the score was a pleasure to write, it was pretty much buried in the final film. Another one of 'life's bitter pills'...Oh well."Tantalizing. Clearly, what Scrooged needs is an in-depth, book-length expose along the lines of The Devil's Candy or Losing the Light (about the making of The Bonfire of the Vanities and The Adventures of Baron Munchausen, respectively). Instead it barely gets two pages in Dennis Perrin's Mr. Mike: The Life and Work of Michael O'Donoghue, which is disappointing because it seems like Perrin could have dug a lot deeper than he did. If there's any one project that could have defined O'Donoghue's post-Saturday Night Live career, then Scrooged, which he co-wrote with frequent writing partner Mitch Glazer, was it.

The film starts off well enough with Elfman's title music over a shot of the clouds as the camera swoops down over Santa's Workshop, which soon comes under attack from black-clad goons with machine guns. Faster than you can say, "It's Lee Majors!" we find out we're watching a promo for a TV-movie called The Night the Reindeer Died, which gives way to spots for Bob Goulet's Old Fashioned Cajun Christmas and, somewhat incongruously, Father Loves Beaver. ("If I know your father, he's out chasing Beaver.") All of these programs are airing on Christmas Eve on IBC, a network run by Frank Cross (Bill Murray), the youngest president in the history of television (as he likes to point out to his underlings), but he's most concerned with the live broadcast of Scrooge which he has staked his reputation on and has devised an apocalyptic TV spot for. This disturbs his programming directors, but only one, a timid executive named Eliot Loudermilk (annoying played by Bobcat Goldthwait substituting for Sam Kinison, who would have been much more interesting in the role), voices his concerns about it ("That thing looked like The Manson Family Christmas Special."), which is enough to get him sacked on the spot. Thus begins Eliot's swift descent into his own personal hell (one where he becomes a raging alcoholic seemingly without being able to take a single drink), which is mirrored by Cross's fall from grace (a process that, it turned out, took a bit longer).

Speaking of Grace, that's the name of Cross's personal secretary (Alfre Woodard), who gets to play the Bob Cratchit role, and her young son, who hasn't spoken since his father died, is the Tiny Tim equivalent (so you know as soon as you meet him what his one and only line is going to be). In short order the film also introduces us to Cross's slightly loopy boss (Robert Mitchum), who's concerned about reaching the underserved pet market; the slick Hollywood hotshot (John Glover), who is rightly seen by Cross as a threat; and his former boss (John Forsythe), who returns in zombie form to tell him about the three ghosts that will be visiting him to show him the error of his ways. Of course, it's not enough for Cross to turn over a new leaf, he also has to reconnect with the kindhearted social worker he dated in the late '60s (Karen Allen) and who left him because he valued his career over their relationship. This is all well and good, and setting the story within the milieu of network television (which O'Donoghue was well versed in thanks to his years in the trenches at SNL -- it's easy to see why the brunt of his ire is directed at an embattled lady from Standards and Practices) was an inspired choice. Then the movie has to bring on the ghosts and, well, the results just aren't pretty.

If you ask me, David Johansen and Carol Kane nearly sink the film as the Ghosts of Christmas Past and Present, respectively. Johansen mugs terribly as a no-nonsense cabbie who drives Cross around, showing him scenes from his childhood (during which his gruff father is played by Murray's older brother, Brian Doyle-Murray), his early years at IBC, his meet-cute with Allen and their subsequent break-up. In contrast, Kane is shrill and giggly and dressed like the Sugar Plum Fairy, which is supposed to make it funny that she beats the living shit out of him, but the schtick gets tiresome fast and the scenes she shows him -- of Woodard's poor but joyful family and his younger brother's (John Murray) holiday gathering, which he was invited to but of course declined -- don't really make up for it. After that the stage is set for the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come to redeem things somewhat. This is by far (and by necessity) the darkest part of the film and there's no overacting going on to distract from how disturbing the imagery is. The scene I'm most taken with in this section is Allen's transformation into a self-centered socialite, but they're all chilling in their own ways and they do the trick. When Frank Cross returns to the real world he's a changed man. Unfortunately he's also completely bonkers -- or at least that's how Murray plays him.

According to Perrin, Murray wanted "a big acting moment" for the scene where he teams up with a shotgun-toting Eliot to hijack the live broadcast so he can announce to the world that he's a changed man. At this point it's worth quoting from Roger Ebert's scathing one-star review:

This sequence is the strangest in the film. The words are there, but the heart is lacking. Murray stands center stage and rants and raves about the spirit of Christmas, but it's not an inspiring speech and certainly not a funny one. It sounds more desperate than anything else, and it continues at embarrassing length. It looks like an on-screen breakdown.Interestingly enough, a breakdown is exactly what screenwriter Mitch Glazer thought Murray was having while he watched the scene being filmed from the sidelines. For his part, O'Donoghue's response was more acerbic. "What was that? The Jim Jones Hour?" he said, a remark that earned him a punch in the arm from director Richard Donner. A perfect encapsulation of the screenwriter-director relationship in Hollywood, perhaps?

Finally, he demands a miracle, and his secretary's little tyke is dragged forward to demonstrate that he can actually speak at last. Then the entire cast and crew line up behind Murray to sing of Christmas cheer, and I can't remember when I've seen anything along these lines that was more forced and depressing.

As Scrooged limps to a close, there's a bizarre Return of the Jedi moment where Cross spies all of the ghosts who have visited him -- including a homeless bum played by Michael J. Pollard who froze to death because Cross refused to give him a handout -- off in the corner of the studio, full of good cheer. Even the tortured souls in the Ghost of Christmas Yet To Come's ribcage have candy canes! (I doubt these rubbery creatures were what earned the film its lone Oscar nomination, which was for makeup. Rather, I suspect Forsythe's much more impressive appearance is what prompted it.) Probably not the ending O'Donoghue (who cameos as a priest in the scene where Cross is shown his own cremation) was hoping for for his only big-budget Hollywood film, but you have to keep in mind that this was a man who gained some measure of notoriety on Saturday Night Live by doing his patented impression of celebrities having nine-inch steel needles plunged into their eyes. After that, merely threatening to staple antlers onto mice was always going to be a step down.

And here we are, my brothers and sisters, at the end of this year-long look back at the films of the 1980s. Maybe if we'd taken a cue from the AV Club and called it Our Year of Eighties we might have gotten a book deal out of it. Who knows what we may have encountered on the road not taken? Despite what the Back to the Future films have been telling you (and did you know that we totally covered one of those?), you simply cannot change the past. You may regret decisions you've made in days gone by, those unfortunate times when you zigged when the situation clearly called for zagging, but what's done is done. The best you can hope to do is learn from past mistakes and make the most of the time you have left on this earth. There is, conveniently enough, a movie which beautifully illustrates this theme. It is called Remains of the Day and stars Anthony Hopkins and Emma Thompson. You can probably have it instantly streamed to your phone or however it is that people watch movies these days. Perhaps by the time your read this article, it will be possible to transmit movies directly to your cerebral cortex. (Oh, god, think of what Madison Ave. could do with that!)

But that theme is also at the heart of Scrooged, Richard Donner's garish, disorganized and yet (occasionally) quite funny 1988 variation on Dickens's immortal A Christmas Carol. Now, I tell you this in the strictest confidence, reader, but it just so happens that I am something of a Christmas Carol fetishist. No, no, I don't have impure thoughts involving plum pudding or fantasies about being tied up by Emily Cratchit or anything like that. I simply mean that I derive an inordinate amount of pleasure from seeing filmed adaptations of A Christmas Carol -- good, bad, and indifferent -- and I have a whole list of specific plot elements which I strongly prefer to see included rather than left on the cutting room floor. Nothing "harshes my mellow," so to speak, more than a Christmas Carol remake which skips over, let's say, the appearance of Ignorance & Want from underneath the robe of the Ghost of Christmas Present. (As a point in its favor, let me say that the recent Jim Carrey version included, hands down, the most elaborate Ignorance & Want scene in movie history.) But even as a fetishist of all things Scrooge-ean, I know enough to cut some slack to Dickens derivatives set in the modern day. I know that in updated parody versions like Scrooged, we're just going to get the broad outlines of the familiar yarn: three ghosts visit a rich miser on Christmas Eve and show him the error of his ways. Sometimes we don't even get that much. In Stan Freberg's controversial 1958 "audio theater" piece called "Green Chri$tma$," the Scrooge character (an advertising executive, natch) doesn't learn his lesson or find redemption at all. Kindly Bob Cratchit glumly accepts defeat in the face of crass commercialism, and the whole record climaxes with an orchestral rendition of "Jingle Bells" obscenely punctuated with cash register noises.

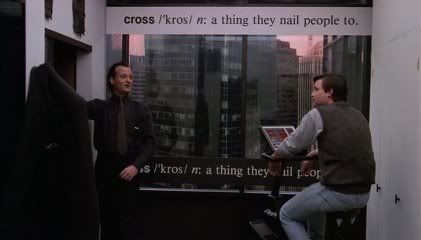

Donner's version of the Dickens tale is quite a bit more forgiving than Freberg's. This being a major studio holiday release, our Scrooge-like protagonist, TV executive Frank Cross (as in "a thing they nail people to"), does see the light by the end of the movie and positively radiates warmth, charity, and goodwill towards men by the time we reach the end credits. In short order, Frank rehires poor Bobcat Goldthwait, rekindles his love affair with doe-eyed do-gooder Karen Allen, and even magically cures Alfre Woodard's son's post-traumatic stress disorder. The good news is that Frank Cross is played by Bill Murray, so we know that even he isn't buying this miraculous transformation. I'm glad Craig brought up Roger Ebert's review of Scrooged because it contains this fascinatingly tone-deaf assessment of Murray's performance:

He's often gruff in his movies, but in a way that lets you know he's just kidding. This time, he doesn't seem to be kidding ... When he shouts at people, he doesn't add a little spin of self-mocking exaggeration, so that we know to laugh. He seems to be really shouting. And the other actors look as if they really feel shouted at.I'm not exactly sure which film Mr. Ebert saw, but it doesn't seem to be the same Scrooged I just watched, in which Frank Cross is such an inveterate wiseacre that we never for a second take him seriously as a soulless corporate villain. If anything, Murray doesn't play the part cruelly enough in the early stages. He doesn't approach Scrooged much differently than he did Stripes or Ghostbusters. We are constantly told that Frank Cross became a network president by working relentlessly and shutting off friends, lovers, and relatives in pursuit of wealth and status, but somehow I never bought it. Frank comes off like such a typical Murray knucklehead, completely ruled by his impulses, smirking at the world, that he hardly seems to have the attention span and laser focus you would need to become a successful television executive. Note how much different Murray's demeanor is from both the old guard (represented by Robert Mitchum and John Forsythe) and the young turks (represented by John Glover). As we'd expect from a Bill Murray movie, Frank is the lone wisecracking kook in a world of suck-ups, stiffs, and stuffed shirts. From my vantage point, Murray behaves pretty much the same way before and after his supposed metamorphosis. The film labors mightily to tug on our heartstrings, what with the traumatized boy who won't speak and the kindly old bum who freezes to death in a sewer (shades of a Groundhog Day subplot?), but Murray seems much more invested in being the consummate class clown. "So much for pathos," as they say on Monty Python. But, again, this isn't a huge problem because we don't watch Scrooged to see a heartless miser learn a lesson; we watch to see Bill Murray do that Bill Murray thing. By the film's very end, Murray seems to have given up on the plot entirely and is quoting Little Shop of Horrors (another film we totally covered) and leading the audience -- the movie audience! -- in a singalong. Murray's film-ending monologue/rant/breakdown may not function as a plausible conclusion to the story -- it far exceeds the limits of plausibility -- but it's a pretty neat performance showcase for the film's star and may actually work better out of context.

For me, Scrooged functions best as a grab bag of rowdy, fast-paced, occasionally rude SNL-style humor, a surprising amount of it successful. Being a 1980s Bill Murray character (setting aside the one he played in The Razor's Edge), Frank Cross is a motormouthed quip machine, and the script generously supplies him with plenty of good lines. There is malicious joy in Murray's voice when Frank lashes out during a board meeting and exclaims, "Now I have to kill all of you!" Ditto when he gives this none-too-inspiring preshow pep talk: "Break a leg, everybody! I feel real weird about tonight." No matter how often we're told that Frank is miserable, it's impossible to believe he's not enjoying these moments just a little. Maybe my favorite scene in the film is the one which has Frank going over his Christmas list with his long-suffering assistant, Grace, and deciding who gets a VCR and who gets a towel. (How delightful to know that Colonel Tom Parker only merits a towel.) In the credit-where-credit-is-due department: Bill's gruff-voiced brother, Brian Doyle-Murray, shines in a flashback scene as little Frank's humorless dad, who gives his son the ultimate Christmas present -- five pounds of veal. And then there is the film's treasure-trove of inside showbiz humor. Hollywood has always been especially adept at mocking its own crassness and shamelessness, and the flashes of tasteless IBC programming we see during the film are a testament to just how low the entertainment industry will sink in its relentless quest for viewers and money. A key element of this type of humor is finding past-their-prime celebrities willing to essentially act as human punchlines, and boy has this film got 'em! I noted with glee that the cast included at least three erstwhile Gong Show regulars: Mabel King, Pat McCormack, and Jamie Farr. If only they could have tracked down Jaye P. Morgan! Meanwhile, the brief Robert Goulet scene caused me to wonder: how much of his life did Mr. Goulet spend parodying himself? My guess: more than he'd planned.

I'm disappointed that Craig was put off by the film's slapstick elements. I more or less delighted in them. I tend to love what Carol Kane calls "the rough stuff" (in comedy if not in life), and I was especially pleased by the fact that not one but two women are participants in the film's slapstick humor, not only Ms. Kane but also Kate McGregor-Stewart as the hapless network censor. Even today, unless they're playing cutely clumsy heroines in romantic comedies, women rarely get to take part in physical humor on screen, so it's a special treat to see them on both the giving and receiving ends of the equation in Scrooged. On the giving side, we have Carol Kane as the Ghost of Christmas Present. Craig says her performance nearly sinks the film, but I distinctly remember that when Scrooged was in theaters (my family and I were among those opening weekend ticket buyers), Kane's extended cameo received an inordinate amount of acclaim and attention. What makes her character, the cheerfully violent Ghost of Christmas Present (notice how Scrooged reverses the traditional genders of the Past and Present ghosts) funny is that Kane plays the role as a dead-on spoof of Billie Burke as Glinda the Good Witch in The Wizard of Oz, even aping one of Burke's famous lines: "I'm a little muddled." That line about being "muddled" is key to both Burke's and Kane's characters. Go back and watch The Wizard of Oz, and you'll find that despite her sweetly confused demeanor, Burke is actually an instigator and a troublemaker, taunting the Wicked Witch and getting Dorothy in trouble in the process. What Kane does is take Glinda's passive aggression and turn it into aggressive aggression, i.e. hitting Bill Murray in the chin with a toaster while smiling vacantly. That's funny enough for me. On the receiving side, poor Kate McGregor-Stewart plays a snooty but hapless network censor who undergoes a Calvary-like gauntlet of physical injuries. Donner and crew must have (correctly) guessed that no one in the audience would mind seeing a censor get knocked around a little.

I cannot, however, defend ex-New York Doll David Johansen's shamelessly hammy performance as the Ghost of Christmas past. I just wanted him off the screen, fast. And I agree that twitchy, fidgety Bobcat Goldthwait is a complete misfire as Eliot Loudermilk, one of the film's two (by my count) Bob Cratchit figures. Craig would have preferred to see Sam Kinison in this role, but I think it cries out for Rick Moranis. Eliot, after all, is a nebbish who gets pushed too far and finally snaps. Aggressive, loud comedians like Goldthwait and Kinison are simply not believable as nebbishes, but Moranis fully embodies the type. Also, since it's so atypical for him, Moranis could possibly have wrung some laughs out of Loudermilk's violent spree towards the end of the film -- a decidedly unfunny sequence with noise and chaos replacing actual comedic ideas. Goldthwait's breakdown is not funny because it's not surprising. In every movie, he always seems to be a few seconds away from a breakdown.

Scrooged is marred by these casting problems, and the script is further hampered by a muddled timeline (confusingly, Frank apparently goes on with his daily life between visits from the ghosts), and an emphasis on simplistic homilies that no one in the cast or crew seems to truly believe. But I was not bored by Scrooged, and the film wisely does not overstay its welcome. In fact, I'd go so far as to name it the second best Christmas Carol adaptation of the 1980s -- behind, of course, the 1984 version with George C. Scott, coincidentally directed by Clive Donner (no relation). Once upon a time, it had been our intention to cover that film for this series on Unloosen, but our Christmas gift to the readers is that we ultimately decided against it.

P.S. - Craig, you said that Scrooged was the only Christmas film that hit you at a gut level. Now, you and I both know that there's a line from Annie Hall which makes an ideal rejoinder to that statement, but I won't use it. Consider that my Christmas gift to you.

Up Next: Nothing! Absolutely nothing!